Last year when some Cholistanis reached a graveyard near Yazman to bury one of their elders who had died, they discovered that their ancestral graveyard has been allotted to a settler from central Punjab who refused them permission for burial. The bereaved family members and friends were infuriated who decided to take up arms. Tension ran high among both the locals and settlers for days until some elders of the area intervened and a fight between the two groups could be avoided.

In the summer of its discontent Cholistan is simmering with protest. And it is the issue of allocation of land to aspirants from outside the area which is central to Cholistan's agonising history. As the process of land distribution keeps pushing ahead at the cost of Cholistanis rights, the anger among the local population matures.

If it is the lack of organizational capacities that has kept Cholistanis from acquiring a political expression so far, the continuous onslaught of what they call as `colonial governance' of the area has made the situation even worse.

If it is the lack of organizational capacities that has kept Cholistanis from acquiring a political expression so far, the continuous onslaught of what they call as `colonial governance' of the area has made the situation even worse.

Cholistan's half a century old experience with the state of Pakistan has not proved to be a prolific one. Fifty years on there is discontent. And it has spilled over from the confines of urban cafes right down to the rigors of desert life. There would hardly be a Cholistani who does not distinguish himself from the rest of Punjab. He almost consciously establishes his identity as Cholistani separate from Punjabi.

Decades of discrimination, it seems, has blurred the vision of Cholistanis who fail to distinguish between the Punjabi speaking bureaucrat who is responsible for their degradation and the Punjabi masses who, ironically are not only suffering at the hand of the same rulers but are also unaware of the situation just a few hundred miles down in their own province. Punjab and Punjabis are the metaphors for oppression and centre of jokes during evening chats in the Cholistan villages.

But this situation is only about 50 years old. At the time when Cholistan was part of the state of Bahawalpur no one was familiar with the difference between Punjabi and Seraiki as Ahmed Bakhsh of Langah remembers. The question of Punjabi-Seraiki was never in our minds before the state was merged into one-unit because we always had our share in development.

There is more than enough evidence in the history that proves that the conditions of Cholistan was not as bad as it became after its merger into For example, when the British government proposed the Sutlej Valley project in 1922 to irrigate the arid zones of Punjab, Rajputana (now called Rajhistan) and Bahawalpur, the blue-print of the project apparently seemed to favour Bikaner state, whose Maharaja was `Prince Charming' of the British at that time. The state of Bahawalpur's Council of Regency came up with an alternative plan in which the interests of their area were also protected. But the state of Bahawalpur was not so strong at that time because Nawab Sadiq Mohammad Khan Abbasi V was a minor then and the state was run by the council. As a result the British could not be convinced to alter the plan. The fact, however remains that the state did resist the effort to infringe on the rights of its people, though because of its weakness at that time it could not do much about it.

But since the merger of state into one-unit and then the province of Punjab, the woes of Cholistan are on the rise. The most important factor that is responsible for the segregation of Cholistanis, has been their inadequate representation in running the affairs of their areas.

Eversince its inclusion into the province of Punjab, Cholistan is divided into more than 24 provincial assembly constituencies from the three districts of Punjab namely, Bahawalpur, Bahawalnagar and Rahimyar Khan that share parts of Cholistan now. Ironically, and according to some intentionally, however Cholistanis actually comprise the minority of all these constituencies. Because none of these constituencies actually fall completely in Cholistan area and only share bits of it along with other main urban areas where settlers reign supreme. For example if in a constituency the total number of voters is one lakh, only 10,000 of it would be Cholistani while the rest would be settlers. An MPA or MNA contesting elections from these constituencies would obviously cater to the needs of settler voters in urban centers and would never bother to even visit the Cholistani voters in far flung desert areas. Primarily because the small number of Cholistani voters in all these constituencies makes them too insignificant to be listened to and the candidates focus on securing the support of bigger number of voters in cities which is vital for winning the polls.

This vicious configuration of constituencies have deprived Cholistanis from having a single MNA or MPA to represent their problems and issues in the assemblies. If Cholistan is made into one National Assembly constituency and three provincial constituencies, at least there would be someone who be in the assembly representing us, says Ahmed Nawaz of Mithri.

Cholistanis have yet to forget the central government's signing of Indus Water Treaty (1960-61) with India as a result of which River Sutlej, the lifeline of the area was cut off and it suffered the most. Ironically there was no representative from Cholistan, the area which was going to be affected the most, in the negotiation of the agreement with India. Without asking us they (the central government of Gen Ayub Khan) had this agreement with India and Sutlej dried up and our agriculture was ruined. Then we were provided water from Chashma-Jehlum Link over which Sindh province made noise. Where should we go, Mohammad Bakhsh a farmer of Mithri points to yet another rather perplexing predicament of the Cholistanis who often find themselves caught in the crossfire between Sindh and Punjab.

Whatever development that has taken place in the rural infrastructure after Pakistan came into being, also have deep-rooted political undertones. The changes in irrigation system of Punjab, for example, are most important to look into since it is the canals which determine the main course of the agrarian society. Though it requires a detail research to ascertain the apparent political bias behind the extension of canal system in Punjab after 1947, it appears most of the expansions have been made to facilitate only a select group of agriculturalists from among a widely diverse population of the province.

And even some of the ordinary Cholistanis can understand this paradox of their history. Perhaps, in their own way. From among the three chaks (villages) namely 14, 15 and 16 near Kuthri, the canal is provided to chak no 14 and 16 where settlers own land while the chak 15 which comes in between the two does not have any canal because it is owned by locals. Now because there is no water in chak 15 the prices of land are very low. The locals will ultimately be forced to sell their land and as soon as settlers will buy it somehow or the other a canal will be brought to this chak, points out Mohammad Bakhsh, a Cholistani farmer.

Where there is Punjabi abadkars there is canal and the most blatant examples of this discrimination are found in Cholistan. This very fact actually shatters the myth that was constructed by British centuries ago and was nurtured by rulers afterwards that only the people of central and eastern Punjab are excellent agriculturalists. If they are supported with all the infrastructure they will obviously be proved as good farmers, says Shehzad Irfan, the youthful Seraiki nationalist and son of renowned local researcher Abdullah Irfan.

Paradoxically enough it were actually the policy perceptions of British who gave preference to one farming community over the other and thereby created the quintessential divide to rule on, which seems to have been persisting even after fifty years of independence. It were the British who graded farmers from central and eastern Punjab as `the best' and arranged their forced settlements in other parts of Punjab. ÃâIn each district there used to be a list of agriculturalist castes and most of the time only people of these castes were trusted with land allocation in the canal colonies while other castes were left out, says Dr Imran Ali, a renowned researcher on Punjab.

It not only helped British to maximise agricultural output but also created the biradari conflicts between these settlers and the locals which helped the rulers to derive their power from this division. The rural Punjab has yet to come out of, for example, the Jat-Arain riddle. So while this policy of British did contribute to economic growth it also created social rigidity, adds Dr Imran Ali. For example in Jehlum area Janglis pasture lands were allocated and when they resorted to crime and violence, they were given some land but only at the tale end of the canal colonies and were pushed to the peripheries, says he.

The British have gone. But their policy perceptions seem well entrenched in the minds of bureaucrats ruling this country. It seems what British did to the Janglis of Jehlum, the bureaucrats of Punjab are doing to Cholistanis as they fear extinction of their pasture land in the wake of auction plans of the government.

But are Cholistanis going to hit back to their oppressors with the vengeance that was once witnessed in the country's history? They cannot because they are not Sindhis or Bengalis, opines Irshad Taunsvi, a well known local intellectual and poet in Bahawalpur. It is extremely difficult for Cholistanis to put up a consolidated resistance because of a number of cultural, geographically and social factors. Firstly there is hardly any middle class to take the lead. Secondly the Cholistani population is scattered on a huge area and it makes it near impossible to mobilise them politically. And then there are certain cultural factors which make Cholistanis very inward looking. The fact that there has hardly been any FIR registered against a Cholistani for years demonstrate their self-contentedness, says he.

Taunsvi's arguments also explain why the Seraiki nationalist forces have so far failed to establish themselves in an area which has an extremely conducive environment for political movements. The absence of proper industry in the urban centres of the South and lack of any sponsorship, the overall politics of the Seraiki nationalists groups have yet to take roots, says he.

Though Seraiki nationalist groups are poised to bang away at the issue of Cholistan as a central theme of their overall movement for the rights of Seraiki people. But their abysmally poor electoral record in the past and complete lack of resources restrict them to merely increasing their nuisance and not political value through such campaigns.

Notwithstanding Seraiki nationalists incapabilities to put up a resistance, sporadic incidents of violence cannot be ruled out in the wake of recent moves to auction the Cholistan land.

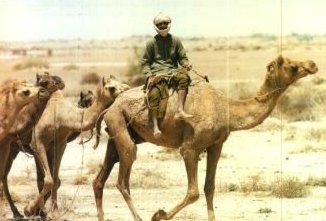

All the numberdars (headmen) of Cholistan are gathering in Bahawalpur this month to decide for future plan of action on the issue. A proposal of staging a protest demonstration in front of the Punjab Assembly building in can be taken up as first step for a movement. Last year a similar plan to launch a march on Islamabad on camel back was postponed at last minute when some local influential intervened.

Apart from this on the chehlum of Abdullah Irfan, a renowned writer who has done extensive research on Cholistan's culture and history, all the Seraiki nationalists groups are planning to reunite this month and launch a campaign on the issue of land allocation in Cholistan. But as Taunsvi explained the Seraiki nationalist groups have very little base in the rural south which still is the political arena for feudal landlords. This factor alone has contributed a lot in restricting the growth of progressive nationalist forces in the area. A feudal MNA or MPA can get a man bailed out from the jail but an educated leader of a small nationalist group cannot! says Ashu Lal Faqir, a Seraiki writer.

Author: Mazhar Zaidi