In one of his interviews, he said his parents had originally named him Ghulam Muhammad. Once when he fell ill, someone said that the name was too heavy for the child and he should be given some lighter name. He was, thus, named Pathana Khan.

Pathanay Khan was born in 1926 in village Basti Tambu Wali, situated in the heart of the Thal Desert, several miles from Kot Addu When he was only a few years old, his father brought his third wife home, so his mother decided to leave his father. She took her son along and went to Kot Addu to stay with her father.

Pathanay Khan was very attached to his mother. She took good care of him, tried to educate him, and gave him the love and protection he needed. However, he inherited many of the attributes of his father, Khameesa Khan. He liked wandering, contemplation, and singing. His nature lured him away from school after Class 7th. Pathana Khans family had no tradition of singing as he belonged to potters’ caste.He began singing, mostly the kafis of Khawaja Ghulam Farid, the famed saint of Bahawalpur , at very tender age. His first teacher was Baba Mir Khan, who taught him everything he knew. Pathanay Khan was poor, and singing alone did not earn him survival, so he started collecting dry logs for his mother, who used to prepare bread for the villagers. This enabled the family to earn a poor living. It is said that remembering those days brought tears to his eyes and he believed that it was his love for God, music, and Khawaja Farid that gave him strength to bear the burden. Pathanay Khan adopted singing as a profession in earnest after his mother’s death. His singing had the capacity to bewitch his listeners, and he could sing for hours on.

Pathanay Khan, a whirlwind-footed darvesh with his beloved friend Yaseen traversed the vastness of deserts, the solitude of wilderness and profusion of urban jungles alike, airing the same message, pulling crowds and establishing a tradition so uniquely his own, that it has probably ended with his own end. Due to his very humane nature, he didn’t refuse invitations from far of places to sing KAFI’s and return with what ever he got. This made him a wondering minstrel, he frequently travelled to all cities of Seraiki wasaib. He was singer of choice on marriage cermonies . A friend of mine once told me that at a times it happened that he was not even paid for travelling expenses by his hosts , despite such unfortunate events he would never refuse to anyone. He indeed was a darvesh , who used to sing for his soul and not for wordly gains.

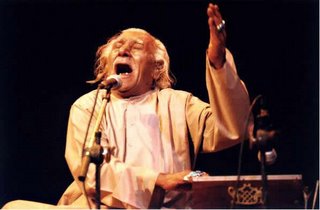

Fewer in the sub-continent would have immersed their entire lives in singing sufi verse so completely, and with such artistic intensity as the late Pathanay Khan who emerged from his virtual anonymity in the 70s to becoming a stylist, an originator and a national asset.Introduced to TV and Radio during the Zulfikar Bhutto period, Pathanay Khan’s singing found its seeds in the human heart, taking from the countless leaves that are words. He created compositions to sing the kalaam of Shah Hussain, Bulleh Shah, Waris Shah, Khwaja Ghulam Farid and Shah Murad, with a haunting potency, unequalled in any of his rivals. While he vastly parlayed with devotional melodies with structures describable as ‘dhun ragas’ includingPahari, Kafi, Des, Yamun and Mand – he also made truly innovative use of seasonal melodies like Malhar and Hindol to sing ecstatically the most uninhibited love of the Divine.Listening to Pathanay Khan’s music is a spiritual and aesthetic experience. His performances were a living manifestation of Dante’s seminal words: “He who would paint a figure, if he cannot be it, cannot paint it.” His resonating voice, the prodigious complexity of his compositions fills the air with mystic worldview of Unity in diversity – the acceptance of the Sacred in the other. What distinguishes him from other sufi-singers was his volcanic creativity, his infinite imagination and its amazing simplicity; his ability to be at once sublimely detached and passionately involved with his surroundings at the time of his performance.

In one of his representative songs ‘Mera ishq wi toon, (you are my only love) with his characteristic stretching of individual words, mid-line breaks, he slowly reveals the identity of his beloved in a rousing wail. The name may never appear in its pure form, perhaps always shrouded in attributes and similes like ‘Zahir,’ ‘Batin,’ ‘Ultimate Beauty,’ – until finally he breaks out in a jubilant rhapsody, repeating the name of his beloved in a kind of magic incantation, enough to produce a music which without exerting force, can move heaven and earth. It wakes the feelings of the unseen with its constant ability to reawaken the listener to an awareness of supra-real dimensions.Often insensitively described as a ‘folk singer,’ Pathanay Khan’s legacy agitates an important debate. Why is it that all classical Punjabi-Saraiki literature is ever so frequently dubbed as ‘folk.’ Punjabi-Saraiki, a language rich in intellectual discourse, the nurturer of a religion and spoken in a vast terrain ought to find such reductionism odious. That it is a rural, sub-urban, rustic and hence a less refined language is a gross  misunderstanding that ought to be corrected. Once this point is established, then one could advance to locate the true position of an artist of such phenomenal creative gift as Pathanay Khan’s. Indeed, with his thorough knowledge of the Shastriya Sangeet and his close association with the Rubaabi gharana which produced such musical talents as ‘Master’ Ghulam Haider (who introduced Noor Jehan and Lata Mangeshkar to Urdu play-back singing and remained an eminent influence on Pathanay Khan’s singing), Baba GA Chishti, Rashid Attre, ‘Master’ Inayat Hussain, Firoz Nizami, ‘Master’ Abdullah and many others – Pathanay Khan’s position as a classical virtuoso could hardly be denied. That he never had to sing ‘Urdu ghazal’ in order to make a back door entry into what is arrogantly assumed as the mainstream is a further proof of his faith in his art.The great 17th century Japanese poet Basho, explained to a disciple that poetry required the poet to abandon his self and become one with nature: “Learn about the pine from the pine, learn about the bamboo from the bamboo…A verse will come when its essence moves you”. For Pathanay Khan this was the only method for his performance. His eyes tightly shut, face drawn away from the audience his lips quavering, his fingers fluttering in the air and his mane of hair flowing – his total consumption in the essence and sonority of what he delivered, seemed majestically tangible. Perhaps someday we will be able to understand more about Pathanay Khan’s spiritual singing and its breathtaking sweep, as a man of acute aesthetic genius.

misunderstanding that ought to be corrected. Once this point is established, then one could advance to locate the true position of an artist of such phenomenal creative gift as Pathanay Khan’s. Indeed, with his thorough knowledge of the Shastriya Sangeet and his close association with the Rubaabi gharana which produced such musical talents as ‘Master’ Ghulam Haider (who introduced Noor Jehan and Lata Mangeshkar to Urdu play-back singing and remained an eminent influence on Pathanay Khan’s singing), Baba GA Chishti, Rashid Attre, ‘Master’ Inayat Hussain, Firoz Nizami, ‘Master’ Abdullah and many others – Pathanay Khan’s position as a classical virtuoso could hardly be denied. That he never had to sing ‘Urdu ghazal’ in order to make a back door entry into what is arrogantly assumed as the mainstream is a further proof of his faith in his art.The great 17th century Japanese poet Basho, explained to a disciple that poetry required the poet to abandon his self and become one with nature: “Learn about the pine from the pine, learn about the bamboo from the bamboo…A verse will come when its essence moves you”. For Pathanay Khan this was the only method for his performance. His eyes tightly shut, face drawn away from the audience his lips quavering, his fingers fluttering in the air and his mane of hair flowing – his total consumption in the essence and sonority of what he delivered, seemed majestically tangible. Perhaps someday we will be able to understand more about Pathanay Khan’s spiritual singing and its breathtaking sweep, as a man of acute aesthetic genius.

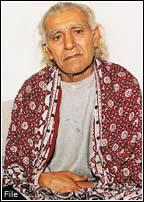

During his last days he fell prey to misery and poverty , this saintly soul had no money to pay for his treatment and was neglected by every one .He died a pauper in his ancestral village at age of 74 on 9th of March , 2000. He left behind 11 children .

Also read About miserable plight of children of Pathana Khan reported by daily DAWN.Click Here.

With Thanks to:

Salman Asif: Based in London, Salman Asif writes on South Asian literary and art history.

Wikipedia.

Daily DAWN.